The Ship of Beautiful Woods

Author’s Note: Among the Queen Mary’s claims to fame are the spectacular veneers used on board. The rarest woods from the vast British Empire were used to make the interiors of the Queen Mary like nothing that had come before. Although the woodwork on board has dimmed with age and lack of care, one can still take the “ship of beautiful woods” tour as described in this pre-war Cunard brochure and wonder at the beauty of her interiors and imagine what they were like when they gleamed as she left John Brown’s yard.

A few areas described in the brochure were removed by Cunard during the ship’s service life, but having recreated this tour with some ship friends while on a visit to the Mary, it is remarkable that so much survived the alterations made in Long Beach.

To see a larger version of each photo, please click on it.

“The sails they were of satin

“The masts they were of gold–”

How does the rest of it go? I forget; it’s a fragment of some nursery book. But it came into my head after reading a more than ordinarily passionate eulogy of the ‘Queen Mary.’

She was this, she was that, the R.M.S. ‘Queen Mary,’ the pride of Britain, the glory of the Cunard White-Star and of all British shipping. She seemed to get as much publicity as the Democratic nominee in an American Presidential Election.

People said “Oo, I should like to see over her.” People said “She must be marvellous.” People said — “Do you know anyone who might — ?” When I actually was invited to visit her in her last days before her builders finally handed her over, a finished masterpiece, to her owners, I felt exceedingly important….

The height of her gave me a crick in my neck. The masts were not of gold. I went aboard.

I expected to see — I don’t know what inside. Perhaps too much splendour. Certainly there was splendour in plenty, but there was far more to her than that.

Leave out the kitchens, the bath-rooms, the stores, the ventilation systems. Concentrate on the decoration of this new departure in ship-building.

Instead of the rococo extravagance that I had half feared to see I found a rich and subtly varied magnificence that contrived to be simple and grand at the same time. If that sounds a contradiction in terms, it is only because most people are not familiar with the means employed in this ship’s decoration.

Grandeur and yet simplicity, splendour and yet exquisite taste–only one medium could perform the miracle.

Wood.

Strange isn’t it, that with all the marvellous new substances of this glittering civilisation one should come back to wood for supreme effects? Here is proof that no modern medium has anything on nature.

Of course there are no clumsy baulks of timber, no such lumps of mahogany that richly held up Victorian dinner parties. These lovely woods are in veneers for which the whole world has been ransacked. Fifty-six of the world’s rarest woods have gone into the adornment of the world’s finest ship–subtly cut into thin sheets, and subtly applied.

Nothing equal to it has been done before–ever.

The term ‘veneer’ must not be misunderstood. A veneer is sometimes ignorantly imagined to describe a sham. In fact, proper veneer is a thin layer of wood that must be either too delicate to be strong in bulk or, indeed, too rare and rich to be used at all, unless spread on some worthy substance (after all, one has to spread caviare on toast). A strong, tough wooden base of no artistic distinction is therefore covered by a thin layer of exquisite wood–as the pillars of the Temple of Solomon were overlaid with fine gold. If the beautiful woods you see on the ‘Queen Mary’ were solid right through, half the forests of the world would have had to be devastated, for some of these veneers will not duplicated in a century

My first visit to the ‘Queen Mary’ was spent in gaping. But I went again, and the second time I procured a guide to tell me what I saw.

One day I hope to travel far enough to see some of these wonders in their native forests.

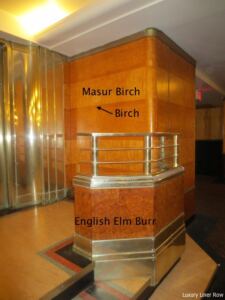

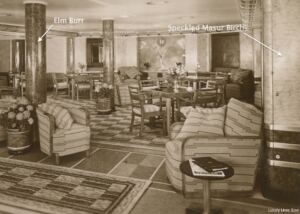

You, when you first go on board, will first see smooth pale walls, faintly speckled, faintly lined. Those walls are masur birch, cross-banded into panels by plain birch. The dark dado below is English elm burr. What is a burr? The excrescence one sometimes see bulging out of the side of a tree. It is very difficult to cut veneer from burrs, but it’s worth doing, and it certainly has been well done here.

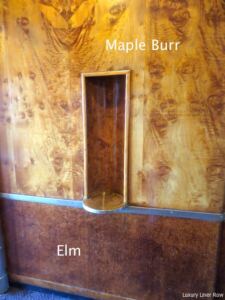

On your left is the great restaurant, a masterpiece. Apart from one or two paintings, everything is left to wood to please and gratify the eye. Peroba wood, light and dark, with here and there a rich panel of maple burr, has indeed made this whole vast hall. Look closely at the peroba. If you have imagination you can see the musical score of a thousand symphonies in the grain, and in the maple burr are inspirations for a whole school of modern surrealist painters. High above you are classical groups, carved in wood, in inspiration ranging from Cleopatra to Chaucer. They are beautifully applied to the flat surface, and actually give the effect of a clerestory. One of them is reproduced on the cover of this book.

Come back now to you starting point, and climb. The main staircase has again a dado of English elm burr, dark and complicated in pattern; above it rise pale walls of mottled, white English ash. The bold pattern is austere, and rightly so; a staircase is not the place to loiter….

So go up the stairs. At each deck is a ‘Square’ panelled in masur birch, banded with plain birch, and a dado of elm burr, until you arrive at the grand main hall on the promenade deck.

Opposite this destination is Queen Mary’s portrait in medallion, surrounded by the richest walnut burr that the world can produce. Blending almost imperceptibly into this surround is a vast panel of English elm burr, and the whole wall stands out magnificently from the white ash on either side.

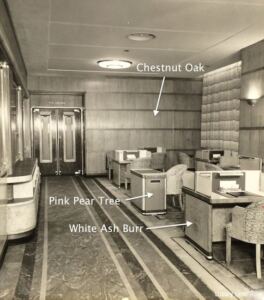

The main hall is where the shops and show-cases stand. Its walls are chestnut oak–a hybrid that seems somehow comfortably English–and the supporting pillars light coloured elm burr. [Note: During the post-World War II refit, the veneer in the Main Hall was covered with alternating strips of colored leather.] It is a vast hall and (whoever feels jealous) the three principle shops ought to be mentioned.

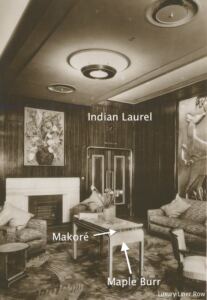

The bookshop is almost startling inside with a wood boldly stripped in gold and brown called makoré. [Note: During the liner’s post-war refit, the book shop was re-veneered in a lighter wood. Almost none of the original wood survives.] The ship’s own cigar shop is lined fragrant cedar and a quilted maple that (believe it or not) looks exactly like quilted silk. The outfitter’s shop is lined with Indian silver greywood relieved by bands of Indian laurel round the skylight.

From here an overwhelming galaxy of wooden beauty waits for you, but before you get tired of colour and grace and pattern I should recommend (as a seasoned visitor by this time) that you descend to ‘A’ deck again. Pass through the inevitable ‘Square’ and glance down the passages of cabins.

Sycamore. Glorious, pale English sycamore panels with a hint of platinum in their sheen, set off by a dado of Australian walnut–both woods laid with their grains horizontal. An almost infinite vista. If you like statistics, let me tell you that there are on the ‘Queen Mary’ no less than sixty thousand feet of this figured sycamore, the cream of over one million and a quarter feet of veneers cut!

How many Englishmen know that English sycamore is something more than a tree? Sycamore grows to perfection in England. The oak, the beech and the walnut may be noble, but the oyster-coloured satin of sycamore is worthy of a queen.

Take that sycamore as a criterion of beauty, compare it with the bird’s-eye maple passages on the main deck (very fine they are, set off with the ruddy African cherry-wood dadoes and door lintels). You will see nothing more pleasing. So feast your eyes, and then prepare for the subtleties of colour and figuring in the great public rooms. Back to the promenade deck. Climb again.

There are entrances from the promenade deck (from here you can see the sea) where the walls are of delicately figured ash, with elm burr dadoes, and door frames subtly lined with straight grain ash. [Note: After World War II, the veneered walls in the Queen Mary’s Main Hall on Promenade Deck were redone in leather, which is still there today.] Pass though them and visit the smoking-room–modestly called the cabin smoking-room.

Here is the richest tiger oak. It is called that because the stripes are tigerish; but the figuring goes further than mere stripes. I found a portrait in this fierce wood of King Henry VIII, obviously taken by Nature during one of His Majesty’s grimmer moments. There is a picture of it in this book. Pillars in this great hall of plain brown oak provide a background, and delicate walnut butt melts on the backs of the chairs. Such walnut butt is cool; it seems almost an olive green against the terrific oak. You’ll notice a great table and side-board of rich walnut burr, cross-banded with plain oak. You’ll notice, at the ‘after’ end, lighter tiger oak panels set off by uprights of brown oak.

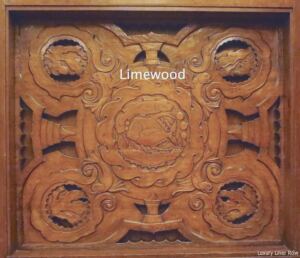

And there is still another interest. Pierced panels of lime-tree, carved and stained and waxed…. Well, after the second day I suppose one would just take them for granted and just smoke.

Now come to the long gallery. You remember the beautiful white figured ash of the entrances from the promenade deck itself (where you can see the sea)? Well, in this long gallery is betula. It is white figured ash that has got to heaven. Not brown, not red–not satin, not silk–a wonder in sheen and swirling figure, on walls and ceiling. Betula is actually the heart-wood of Canadian birch. The doors are of figured makoré–sombrely and darkly lined–and two have an inner frame of maple burr. These names may bewilder, but beauty cannot afford to be anonymous. Underneath the show-cases in this gallery are maple burr panels, pale and demure.

You’ll find rare and beautiful makoré round the gallery in the ball-room and on the ball-room doors.

Go across to the starboard gallery. Here is brown Indian laurel wood; the tables are of maple burr again, cross-banded with the same makoré. The huge fawns and palms in this gallery are painted in gold and silver, but they were carved from Honduras mahogany.

The passage between this gallery and the great lounge is lined with pale mahogany, and the doors and lintels are called pommelé. Some people name this would blistered sapelé mahogany, because the figure of this curious wood conveys the illusion of bubbles rising from a cauldron–of blisters that one almost tries to burst. But, anyway, pommelé is shorter.

The lounge itself – a vast, lofty hall – is stupendous. The walls are of maple burr – a rosy maple burr – and the ceiling and ornamental recesses are masur birch which looks pale, delicate and cool, so that one almost misses its mottled figure in all the height and distance. Tables are of maple burr surrounded with walnut and sycamore. But the great pillars are of makoré. A different makoré, this time. A makoré that could not be matched again if every country were ransacked – rose red with deep brown lines. This is a majestic wood.

The cabin writing-room (you and I might ignorantly call it the first class writing-room) is subdued: chestnut oak walls, and white ash burr on the tables. They are fitted with pink pear-tree letter boxes and banded in the same cheerfulness. That white ash burr is very contemplative; it’s swirling lines reminded me of a millpond in late Summer.

In the music studio – you can’t miss it – the walls are of a figured sycamore, perhaps rather less virginal then the shining wood in “A” deck corridors. Then in the passage that leads to the observation lounge and cocktail bar, over the elm dado, subduing the elm doors, is a maple burr that blazes like an Eastern sunrise. Look well at that maple burr. It has puzzled many experts. In generations we shall not find its equal.

The cocktail bar and observation lounge itself unbends to funny pictures, but the walls are of maple, figured almost like a tiger oak though rather lighter. The bar is of striped macassar ebony, golden and black, and the plinth of the gallery and the banding that cuts the maple walls into long panels is made of a weirdly mottled wood – rust-red ovals, spheroids and circles on a pale ground. This is unknown in botany. This is a forest monster. Is it cedar or mahogany? They call it cedarmah.

Left: The port aft corner of the room.

Right: The bar with A.R. Thomson’s Royal Jubilee Week, 1935, above.

The drawing-room is not exotic. It is very sophisticated and feminine. The tabletops and the backs of the chairs are maidu burr. Look at the prim little curls in this wood. They would be the despair of a hairdresser of the First Empire.

I cannot pour out endlessly the names of every shade of wood at every turn of every passage, at every staircase, almost every stair. You would be exhausted, deafened, and you might miss some beauties altogether. Rest for a little in the library where there is just a soft blending of light and dark oak burr and pollard oak and combed oak (with a band–no more– of macassar ebony at the table bottoms) and observe how the brown-greys and the grey-browns conduce to quiet reflection. See here into the mood your Victorian great-grand parents liked to call a brown study….

But I think you ought to visit the tourist and even the third class public rooms, after a short rest.

Take the tourist part first.

Do you like the grey, bird’s-eye maple and the curly white ash burr of the tourist dining room? You’ll certainly love the quilted figuring of Pacific maple with the dado of Nigerian ‘drappé’ mahogany (it looks like some silken fabric) in the tourist entrances.

In the tourist lounge on ‘A’ deck, note the elm burr pillars and the walls of speckled masur birch.

Then in the main tourist lounge, when you have ignored the peculiar greenish leather walls, note the bands of sycamore, maple burr and thuya, then maple burr, and so to sycamore again. What is thuya? It’s dark and red and African, and lives like the ostriches in sand.

That puckered, pleasing, pale gold wood on the outside of the doors is maple–quilted maple again. And it persists on the entrances from the tourist promenade deck, enhanced here with a dado of Nigerian drappé mahogany, almost metallic in its sheen, and the colour of old gold.

Evidently the tourist passengers have not been overlooked. In these entrances are four very charming nymphs, carved in willow. I should have thought the cabin passengers might have enjoyed them – but no matter.

The tourist smoking-room? Of course. A lovely figured burr of British brown oak – relieved by Indian golden padouk. A learnéd room; a very dignified room.

Third class? In their garden lounge is a garden scene in marquetry that is really lovely. In their smoking-room is a hunting scene, too, in coloured woods. The walls and the passages are richly veneered…. Beauty on this ship is displayed for everyone.

The cabins and suites in the cabin part of the ship (you and I, remember, would probably call them in our ignorance first class) deserve a book to themselves. It is quite impossible to do them detailed justice here. And as at the back of this hasty description is a more detailed list of woods to be found throughout the ship, I will not attempt the impossible.

But I must note a few of these private rooms that I particularly liked. I shall take them at random, and if you follow me – since you have seen the staircases – by all means take a lift. Indeed, you must see the lift because (although they are called elevators) they are very fine with white ash burr roofs, and walls deep red with elm burr, banded at the top in walnut.

The entrance to M55 and M57 (‘M’ means main deck, of course) is panelled in gorgeous sheets of figured English sycamore, and in this entrance is a charming marquetry panel [Note: This is now lost], which indeed I have had photographed, made up of ten natural woods. The background is oak. One tree is rich walnut, the other olive ash, and you can pick out (if you are clever) white birch, dark birch, pear-tree, blistered maple, oyster ash, plain ash, light walnut. The rooms themselves are beautiful, but less remarkable.

The entrance to suite M65–67 [sic] is rosy pear-tree – like a rising sun at Suez – and a walnut cat sleeps through all the splendour. There is a dado of vividly striped corbaril wood. The main bedroom (M67) is panelled in masur birch, which here is as speckled as a speckled hen. M69 is white ash, beautifully figured like a thousand swirling whirlpools. Oaken pillars frame the entrance to a dining-room, M71, with sliding doors of a pale ash that shows an amazing olive figure. In this room are tables of Bombay rosewood curl – a very rare wood of glorious deep purple. At such a table one would be compelled to drink Veuve Clicquot.

In M73 is a table of Queensland maple butt, a glory of pink satin figured as no weaver could imagine, and shining as no satin could shine.

M77 has an entrance of weathered sycamore where an extraordinary effect has been attained by exploiting a natural stain in the wood. Inside is weathered sycamore – deep cream-coloured – with a wonderful curl in its figure. The furniture of walnut and sycamore is a harmony of soft tones.

M105 is avodiré — a golden, silvery wood with flecks of cloud like smoke drifting over a prairie fire. The furniture of olive ash burr salaams to it.

Some cabins have fabric walls with beautiful veneered dadoes. Some have painted walls with lovely wood below. M14 has walls of bird’s-eye maple with a pinky-cream background, which looks just like the stiff, prim, rosy silk that should make an early Victorian hooped skirt. You can see nearby a cabin of very plain old with horizontal lines – a cabin absolute harmony, waiting, a perfect background for some very pretty person.

M50 is a charming little room, all in white sycamore, with quaint little natural, fish-like markings here and there.

Only one cabin I did not like. You may disagree with me, M79. The entrance is pleasing enough. It is fiddle-mottled walnut, decorated with two old carved oak figures, one representing St. Christopher – it’s in this book, on page 3 – patron saint of travelers. [Note: This carving is now lost.] But M79 itself inside is panelled in East Indian satinwood. East Indian satinwood is too often distorted by native cabinet-makers into inconvenient furniture. Anyway, it carries here unnecessary paintings in blue lines (or are they green?). The beds are very purple – bubinga, I believe.

For my part I should choose A44. Its walls are Queensland maple butt, rosy as the morning and figured like an ancient tapestry. The furniture is blistered cedar.

The only trouble would be that, with such a cabin, one would never wish to go on deck!

Nobody has built a ship like this before. Nobody before has thought of using the simplicity of nature to create beauty. Every intelligent personality can find on the ‘Queen Mary’ its ideal physical background.

This is the ship of beautiful woods, and it is more than that. It is the ship of beauty. Alas, that it should be so swift one will never be able to stay long enough on board.