A Titanic Mystery

by Eric Sauder and Brian Hawley.

In the early morning of April 15, 1912, a young man died from exposure in the middle of the Atlantic after the ill-fated White Star liner Titanic struck an iceberg and sank on her maiden voyage. One of 1,496 victims, Edwin Charles Wheeler’s name is familiar to many Titanic researchers, but he is one passenger about whom little is known. There are precious few mentions of Wheeler by name in the 1912 reports of the sinking. One is in a very brief newspaper account that appeared in The New York Times, and another is on the official Titanic passenger and crew list used by the U.S. Senate at the inquiry into the sinking, which lists him simply as “Mr. Vanderbilt’s servant.” The few tantalizing details available made us wonder: Who was this relatively anonymous man traveling alone on the largest ship in the world and why was he there?

Edwin Charles Wheeler was born in Bath, England, on February 19, 1886 [1], to Frederick William Wheeler [2] and Emma Wheeler (née Rowlands)[3, 4], part of the vast class of working poor in Victorian England. Frederick and Emma had married in the Register Office on December 31, 1879 [5], and by the time Edwin was born, the Wheelers had been married for over six years. The couple had already lost two daughters, Frederica and Ida Egeria, and Edwin was the first child to survive infancy. His birth was registered on April 8, 1886 [6], and at the time the family lived at 7 New Orchard Street [7]. Edwin’s father was a tailor [8] as were many of his relatives, and he was named after his paternal grandfather Edwin [9] and his uncle Charles [10, 11].

On June 19, 1888, a sister was welcomed into the household and named Maud Lilian [12] (who later went by “Lily” [13]).

A few years later on March 23, 1891, Elsie, a second sister, was born [14]. Unfortunately, the Wheeler family’s happiness at Elsie’s birth was short lived. It seems that Emma may have died shortly after Elsie’s birth although no record of her passing can be found. Emma simply stops being mentioned in any official records [15]. The last official reference to her that can be located is the 1891 U.K. census, which was conducted about two weeks after Elsie was born [16]. Shortly after Emma’s death (or perhaps “disappearance” is a better word), Frederick became ill and passed away from phthisis [17] (more commonly known as tuberculosis) on September 10, 1892 [18], at the age of only 33.

With both of their parents gone, the children were placed in the Union Workhouse Odd Down in Bath [19], which is now part of St. Martin’s Hospital.

Sanitary conditions in 19th-century workhouses were appalling, and in the days before antibiotics, disease spread quickly. Just 2½ years after her father’s death, Elsie died of pertussis (or whooping cough) and convulsions on February 27, 1895 [20], just one month shy of her fourth birthday. The death was registered on March 6 by Mr. Eddolls [21], the master of the workhouse. Within four years, both of Edwin’s parents as well as one of his surviving sisters had died, and he now had to fend for himself and Lily.

Because both children were under 9 years old, Edwin and Lily probably continued to live in the workhouse for a number of years, but by the time Edwin was 15, his prospects had begun to improve as he had become an errand boy at Highbury House in Bath [22], which may have been a residence where young men could learn the skills they needed to go into service for a wealthy family. This type of training was especially important for someone like Wheeler, who had few prospects for advancement. By 1901, Lily had gone to live with her aunt and uncle. She married in 1908 [23] and passed away in 1974 [24].

Records for Edwin Wheeler’s life during the first decade of the 20th century are, for all intents and purposes, non-existent. It is almost certain that he went into service directly from Highbury House and became one of the large army of anonymous footmen in Edwardian England. The next confirmed “sighting” of Wheeler is ten years later on a passenger manifest for the Majestic in 1911. The White Star liner sailed from Southampton, England, on March 29, and arrived in New York a week later [25].

Incoming passenger manifests to the United States are a wealth of information because each non-U.S. citizen entering the country is required to list the “name and complete address of the nearest relative or friend in country whence alien came.” Interestingly, Wheeler listed his contact as H. Pridmore, 42 Bramber Road, West Kensington, London, rather than his sister Lily, who was still living in Bath. At the time of the Majestic crossing, Wheeler was 26 years old, and the passenger manifest shows him as single. He gave his height as a fairly tall 5’ 10½” with dark hair and dark eyes, and his occupation was listed as “manservant.” [26]

Why was Wheeler traveling to the United States when he had no known or obvious connection to this country? Was he, like so many other immigrants, simply taking a chance and coming to America with the hope of a better life? Or had he already secured a position in the States? The answer lies in a single name on Majestic’s passenger manifest.

Listed as Wheeler’s contact in the United States is a gentleman named Talbot Root, of 62 Broadway, New York [27]. Most Titanic researchers would simply look past the name not realizing its significance; however, that was the key that allowed us to unlock why Wheeler originally came to the U.S. in 1911. We will look at Mr. Root in more detail later.

It is commonly said that Edwin Wheeler was the “valet” for a Mr. Vanderbilt, but there has been some confusion over the years about exactly which “Mr. Vanderbilt” this may have been. Until now, no official written documentation had been found linking Wheeler to a specific member of the Vanderbilt family. The only mentions that could be found were a brief article in The New York Times and the Senate Titanic passenger list mentioned earlier. Confusingly, in the Senate list, Wheeler is listed simply as “Mr. Vanderbilt’s Servant,” but again which Mr. Vanderbilt?

The two most likely candidates are Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt, great grandson of “Commodore” Cornelius Vanderbilt (founder of the dynasty); and George Washington Vanderbilt, grandson of “The Commodore.”

We know that Alfred Vanderbilt’s family was concerned that he had been aboard the lost liner. The Baltimore Sun reported on April 16 that Captain Isaac E. Emerson, Alfred’s father-in-law, received a cable from Alfred in response to Emerson’s asking if the rumors of Alfred and his wife being on board Titanic were true. It said:

“Margaret well; not on Titanic. Alfred.”

The Baltimore Sun wrote:

“All of the cabled lists of passengers on the Titanic given out by the White Star Line officials had on them the names of Mr. and Mrs. Vanderbilt. The only explanation which friends of the Vanderbilts can give is that they may have intended to sail on the Titanic and changed their minds at the last moment. Mrs. Emelie A. Emerson, mother of Mrs. Vanderbilt, said she had received a letter from her daughter last week in which she wrote that while Mr. Vanderbilt and she had made their plans until April 1 they were undecided what they would do after that.”

Although spared the horror of the Titanic disaster, Alfred lost his life just three years later when the Cunard liner Lusitania was torpedoed and sunk by a German submarine on May 7, 1915.

A newspaper article which appeared in The New York Times after Titanic foundered mentioned George Vanderbilt by name as having canceled his passage on the doomed liner. Adding to the confusion of which Vanderbilt was booked on Titanic is a letter written after the sinking by one of George’s nieces, which read in part:

“On receiving news of the disaster which happened to the Titanic I at once thought of you and my mind was relieved when I got a letter…that same morning saying that you were on the Olympic….”

Both Alfred’s and George’s close family members (as well as two major newspapers) thought each was to have sailed on Titanic, but which one had actually booked passage? Adding to this, neither George nor Alfred sailed. The question then remains: Who did Edwin Wheeler work for?

Our research has uncovered documents which show conclusively that it was George Vanderbilt who had booked passage on Titanic with his wife Edith and daughter Cornelia.

In the archives of Vanderbilt’s Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina, a letter dated February 6, 1912, has been found which George Vanderbilt himself wrote from Paris to his Estate Manager, Chauncey Beadle, to advise Beadle about his upcoming travel arrangements and that the family intended to sail on Titanic.

Feb 6 1912

Paris 37 rue La Perouse

Dear Mr. Beadle

I am remaining here a few weeks longer than I first intended and have practically decided to sail April 10th on the maiden trip of the Titanic & will come directly to Biltmore after landing….

Most sincerely yours,

Geo. W. Vanderbilt

To which Beadle replied on February 20:

Dear Mr. Vanderbilt –

I am grateful to receive your letter of Feb. 6th….

I note what you say in regard to the delay in your home-coming, and of your contemplated voyage on the maiden trip of the Titanic…. and then too a trip on the Titanic reminds me of the wonderful experience Mrs. Beadle and I enjoyed on the sister-ship Olympic. It is truly a wonderful experience on a floating city.

Faithfully yours,

CD Beadle

Just over a month later, on March 29, Vanderbilt confirmed in a letter sent to Beadle from Paris that he still planned to sail on Titanic:

Dear Mr. Beadle,

…I expect to reach Biltmore April 19th or 20th & will go directly from the steamer to the Hotel Shoreham in Washington. Sailing on Titanic April 10th….

Yours sincerely,

Geo. W. Vanderbilt

As preparations were made at Biltmore for the Vanderbilts return around the 19th or 20th of April, Beadle unexpectedly received a telegram from Mr. Vanderbilt late in the evening of April 2 to let him know that the sailing had been changed at the last minute from Titanic to Olympic, which was departing Southampton a week earlier. The following day, Beadle wrote to Mrs. King, the head housekeeper at the Estate, to let her know that the Vanderbilts were returning earlier than expected and that the preparations for their arrival had to be moved forward a week.

April 3rd, 1912

Mrs. King

Biltmore House.

Dear Mrs. King, –

A cable message received late last night from Mr. Vanderbilt contains the following message for you.

Tell Mrs. King we are sailing on S. S. Olympic April 3rd. Will arrive Biltmore April 13th. Cook and kitchen maid should arrive Biltmore twelfth. My letter referred to later arrival but plans changed.

The above is not literal wording of the message, but is what I interpret therefrom. Unfortunately I left the message at home this morning but I thought best to give you the information at the earliest moment.

Truly yours,

CD Beadle

Shortly after returning home to Biltmore, George Vanderbilt received a letter from his niece Adele Sloane Burden. Dated April 22, it reads in part:

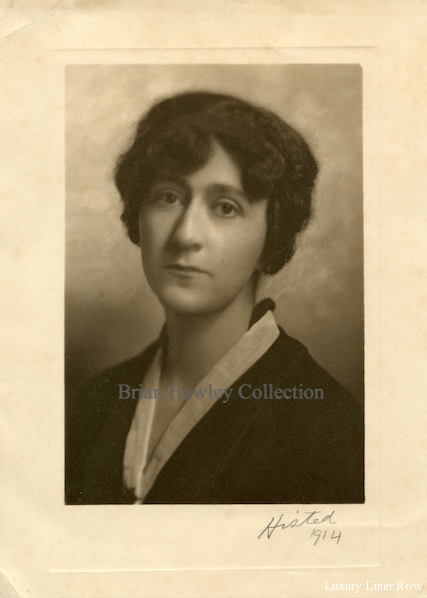

Edith Shepard Fabbri ( left) and Florence Adele Sloane, two of George Vanderbilt’s nieces, in 1894. Edith is still dressed in mourning for her father who died suddenly the year before. George and Edith Vanderbilt sailed on Olympic with Edith Fabbri and her husband Ernesto. Shortly after the Titanic disaster, George received a letter from Adele expressing her relief that he was not on the lost liner.

My dear George,

On receiving news of the disaster which happened to the “Titanic,” I at once thought of you & my mind was relieved when I got a letter from Jennie [28] on the same morning … saying that you were on the “Olympic”. That was a burden off my heart I can say, for although I had not seen details I imagined it must have been pretty bad to have been obliged to put the women & children in boats. But when the details came dear George it was beyond anything thus known so far. There are no words to describe it. There seemed to have been perfect discipline amongst the crew & passengers too. We cannot be too thankful that you were safe on the “Olympic”! <snip>

Love to you all,

Yours afftly,

Adele

With this new evidence, there is now firm proof in George Vanderbilt’s own hand that he and his family were to have sailed on Titanic. The sudden change in plans very likely saved at least George’s life (and perhaps Edith’s and Cornelia’s) because around 70% of first-class men were lost when Titanic foundered. There is a very good chance that, had George Vanderbilt been aboard, he would have perished in the sinking.

Talbot Root, referred to earlier as the U.S. contact listed for Wheeler on the Majestic manifest, was an attorney who not only managed George Vanderbilt’s New York and Maine real estate properties but also served as an import agent who coordinated some of Vanderbilt’s shipments abroad and arranged transportation for domestic servants traveling between Vanderbilt’s homes in New York, Bar Harbor, and Biltmore. Only someone who has a fairly deep interest in George Vanderbilt’s business dealings would recognize the significance of the name and know how Root was associated with him.

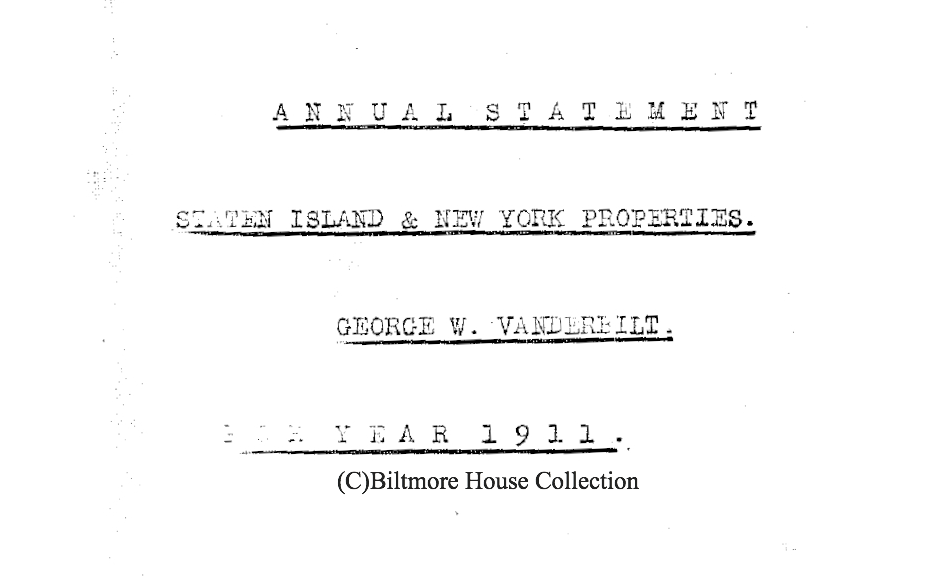

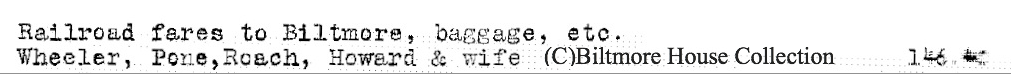

The detailed examination of the Majestic passenger manifest and the information we gleaned from it gave the curatorial staff at Biltmore Estate the information they needed to track down a document in their archive that mentions Edwin Wheeler. It is a 1911 accounting statement that shows that Root had arranged rail transportation to Biltmore for Edwin Wheeler and several other servants after they had arrived in New York on board Majestic. We had tracked Wheeler as far as New York, but this document gave us the evidence which had been lacking to show that Wheeler actually went to Biltmore Estate and worked for George Vanderbilt.

Now that the connection between Wheeler and Vanderbilt finally had been firmly established, we wondered what exactly did Wheeler do for George Vanderbilt? Wheeler has been listed in various sources as a “valet,” “manservant,” “footman,” and simply as “servant.”

Once again the surviving passenger manifests provide a clear answer. From the March 31, 1911, manifest of the Kaiserin Auguste Victoria (Southampton to New York), we know that George Vanderbilt’s valet was Horace Pridmore, and he appears again as Vanderbilt’s valet on the April 3, 1912, manifest of Olympic. As Vanderbilt didn’t need two valets, it is certain that Wheeler was not his valet but was likely a footman.

This is the proof that Edwin Wheeler worked for George Vanderbilt and is the only known mention of Wheeler in the Estate’s archives.

One other point that should be made is that Wheeler and Horace Pridmore certainly knew each other before Wheeler embarked on Majestic in 1911 because Wheeler listed Pridmore as his U.K. contact on the Majestic manifest mentioned earlier. Not only that, they both listed the same address in London on their respective manifests — 42 Bramber Road. How they first came to know each other is still a mystery, but Wheeler and Pridmore must have been in service together at that address, and it may have been Pridmore who recommended Wheeler for the job with Vanderbilt.

In great contrast to Edwin Wheeler’s extremely humble beginnings, George Washington Vanderbilt, son of William Henry Vanderbilt, was born into almost-royal opulence. At the time of his death in 1885, William Henry Vanderbilt was the wealthiest man in the world, leaving a fortune estimated at $200,000,000 in non-inflated gold dollars. By 1885, George Vanderbilt had inherited or been given $13,000,000 of that fortune.

A very wealthy man by any standard, soon after his father’s death, George Vanderbilt began planning a mansion in Asheville, North Carolina. Building Biltmore House, still the largest private home in America, is where he spent a large part of his inheritance.

The Vanderbilts had gone to Europe late in 1910. The detailed examination we conducted of Majestic’s March 29, 1911, passenger manifest showed that two other passengers besides Wheeler listed Talbot Root as their contact in the United States. Because we now know about these other two newly hired servants — they stated on the manifest that they had never been to the U.S. before — this leads us to the conclusion that George Vanderbilt had been hiring staff in Europe during this trip.

After several months in Paris and London, on March 31, 1911, the Vanderbilts returned to the United States on the German liner Kaiserin Auguste Victoria. The manifest for that voyage shows that Pridmore had never been to the United States before, meaning that he had also recently been hired. Wheeler and the two other new female servants, however, sailed on the Majestic, a less-expensive, second-line ship.

One remaining question is why George and Edith Vanderbilt changed their reservations from Titanic to Olympic on such short notice. Remember that George Vanderbilt had sent a letter on March 29 to Chauncey Beadle confirming that the family was sailing on Titanic. Then, within a few days of that, on April 2, Beadle received a telegram advising him of the change in plans and that the Vanderbilts were sailing on Olympic. What could have happened in those few days?

Olympic arriving on April 10, 1912, the same day Titanic sailed from Southampton. Among the passengers lining the rails may be the Vanderbilts.

There are several possibilities, but let’s first look at one that can be easily discounted. On April 30, 1912, two weeks after Titanic foundered, an article appeared in The New York Times stating that a Mrs. Dresser, who was said to be Edith Vanderbilt’s mother, had convinced the couple not to sail.

“Mr. and Mrs. George W. Vanderbilt were saved from the Titanic disaster by the remonstrances of Mrs. Vanderbilt’s mother, Mrs. Dresser, against their sailing, according to intimate friends here.

The Vanderbilts had booked passage on the Titanic and had sent much of their baggage on board in charge of the footman, Frederic [sic] Wheeler. When Mrs. Dresser heard of the arrangement she was much distressed, declaring that the first trip of any ship was dangerous. Her objections were so insistent that her daughter and son-in-law yielded to them, cancelled their passage, and booked on the Olympic, to which their baggage was transferred.”

In the early 20th century, any member of the Vanderbilt family was constant newspaper fodder. Much like Hollywood stars of today, one could count on many stories being printed about them that had significant errors in the reporting. Aside from the obvious mistake in the article which first states that “much of their baggage” was on board Titanic and was being looked after by Wheeler and then states that “their baggage was transferred” to Olympic, there is issue of Edith Vanderbilt’s mother, Mrs. Dresser. We don’t know who the “intimate friends” are from whom The New York Times got the information about Mrs. Dresser, but they couldn’t have been that intimate. Mrs. Vanderbilt’s mother, Susan Dresser, had died in 1883.

Perhaps the Vanderbilts changed their booking to Olympic for the simple reason that George Vanderbilt’s niece, Edith Shepard Fabbri, was sailing on Olympic with her family. Since Edith Fabbri was one of Edith Vanderbilt’s closest friends, they may have just wanted to spend the week-long crossing with family.

Another possible reason for the last-minute change might be that the Vanderbilts were simply concerned that they would be delayed in the UK for an unknown period of time because of the on-going coal strike. Sailings were canceled, and a large number of vessels had been laid up. The strike was causing havoc with Atlantic passenger shipping out of Southampton and Liverpool, and many vessels were unable to sail simply because there wasn’t enough coal to go around. By the time the Vanderbilts changed their passage to Olympic, on April 2, the strike was still not over, and George Vanderbilt, not knowing when he and his family would be able to get home, took the sure thing and changed their passage to Olympic, which they knew would sail as scheduled. Although it doesn’t seem likely that the maiden voyage of Titanic, the largest ship in the world, would have been delayed, the Vanderbilts probably didn’t want to take the chance that she wouldn’t sail had the strike continued [29].

So why did Wheeler sail alone on Titanic while the rest of the traveling party sailed on Olympic? Wheeler boarded Titanic on April 10 as a second-class passenger on ticket #2159 at a cost of £12 17s 6d. More than a century after the sinking, we may never know for sure why he was unlucky enough to board the ill-fated liner alone, but there are two possible reasons.

A man believed to be Edwin Wheeler walking along the second-class Boat Deck of Titanic with Elsie and Ada Doling while the ship was anchored near Queenstown (now Cóbh), Ireland.

After the disaster, a magazine ran the following brief blurb:

“Mr. and Mrs. George W. Vanderbilt and their daughter, Miss Cornelia, after spending the winter in Paris, are again at Biltmore House, congratulating themselves upon their narrow escape from sailing on the Titanic. Their plans were all made to book passage on the ill-fated steamer, but Mr. Vanderbilt, fearing the coal strike might cause delay in the sailing of the vessel, persuaded Mrs. Vanderbilt, at a few days’ notice, to get ready for the Olympic. Their man, who waited over to look after some of their baggage, was lost.”

Because of the sudden change in the Vanderbilts’ plans, there was the difficult question of luggage to consider. The Vanderbilts had spent several months in Europe and had a large number of the obligatory steamer trunks with which the wealthy traveled in 1912. Not only did the trunks have to be packed, they had to be transported from London to Southampton and then loaded on board Olympic. Assuming they made the decision to change their reservations on April 1, that gave the servants only a single full day to pack everything the family had with them and get it all to Southampton before departure. Perhaps Wheeler was left behind in London to finish packing George Vanderbilt’s trunks and to forward the remaining luggage to Titanic.

The problem with the theory of leaving Wheeler to sail on Titanic to accompany some of the luggage as the main reason Wheeler stayed behind is that there was no need for Wheeler to have accompanied any of the Vanderbilts’ trunks. George Vanderbilt had been sailing on White Star ships for decades, and his staff could easily have made arrangements for White Star to ship his baggage on Titanic. When the pieces arrived in New York, Talbot Root could have shipped the trunks to Biltmore Estate. Also, Wheeler didn’t need to “accompany” the luggage because, once on board, he would not have access to it because the pieces were stored in one of the cargo holds, which could not be entered by passengers.

What seems to be the mostly likely reason for Wheeler’s not sailing with the Vanderbilts on Olympic was simple. He may have been in Bath visiting his sister Lily. Because the Vanderbilt party was not supposed to sail on Titanic until April 10, George Vanderbilt may have given Wheeler time off to visit his sister while he was in the UK. Once the reservations had been switched to Olympic at the last minute, Vanderbilt may have told Wheeler to go ahead with his visit to Bath and to keep his existing reservation on Titanic. Of course, unless some documentation is found, at this point, all we can do is speculate on the tragic turn of events although the research continues.

No known written Titanic survivor account mentions Edwin Wheeler; so no record exists of what he did on board or how he spent his final days. What is certain is that Edwin Charles Wheeler, a poor orphan from Bath, boarded Titanic with the hope of a long and happy life in the United States. Tragically, that dream was cut short just after 2:20 on the morning of April 15, 1912. Despite the recovery of over 300 bodies after the disaster, Wheeler was never identified if he were even found. His name lives on because of his connection with the most well-known maritime disaster in history and now because of his recently discovered close connection to one of the wealthiest men in America, George Washington Vanderbilt.

A previously unknown photo of Edwin Wheeler in his footman’s livery that was discovered by us while researching this article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

So much misinformation and rumor has been circulated and printed about Edwin Wheeler that we wanted to discard everything that was ”known” about him and start from scratch, hopefully giving an accurate (albeit brief) record of one of Titanic’s most-elusive passengers.

Researching an article like this takes the help of many people. Above all, however, Alexandra Churchill deserves special recognition for her help with the British side of the research, for figuring out ways around some seemingly dead ends, and for locating the only known photos of Edwin Wheeler in his footman’s livery.

Thanks also go to Darren Poupore, Ellen Rickman, Lori Garst, Laura Overbey, and Leslie Klingner at Biltmore Estate for their kind assistance in using the information the authors supplied to sift through the Estate’s archive to find the documents that positively linked George Vanderbilt to Edwin Wheeler. www.biltmore.com

The authors would also like to express their thanks to Mary Kellogg-Joslyn, John Joslyn, and Paul Burns of the Titanic museums in Branson, MO, and Pigeon Forge, TN. www.titanicbranson.com and www.titanicpigeonforge.com

Finally, appreciation to George Behe, Dan Cherry, Tad Fitch, Don Lynch, Mike Poirier, John Rawlings, Chris Sauder, and the Titanic Historical Society for their efforts on our behalf.

FOOTNOTES

1. Birth Certificate for Edwin Charles Wheeler.

2. Birth certificate for Frederick William Wheeler.

3. Emma Wheeler’s maiden name is listed on various official documents as “Rowlands,” “Rowland,” “Rolands,” and “Roland.” This spelling used in the article is taken from her marriage certificate.

4. Throughout the research for this article, the names of many of Wheeler’s relatives have caused problems because they are listed with different names on different official documents. The authors have used the names as given on each person’s birth certificates where available.

5. Marriage Certificate for Frederick William Wheeler and Emma Rowlands. On their marriage certificate, the ages given for Frederick and Emma were 22 and 23 respectively, and no profession is listed for Emma Wheeler. The service was conducted by R.H.Carpenter, the Registrar, and two witnesses were present — Ellen Golledge and Louisa Mitchell.

6. Birth Certificate for Edwin Charles Wheeler

7. Birth Certificate for Edwin Charles Wheeler

8. Birth Certificate for Edwin Charles Wheeler

9. Birth Certificate for Frederick William Wheeler

10. Birth Certificate for Charles Wheeler

11. For many years, Titanic researchers have also known Wheeler as “Fred,” but this was not his given name and may have been a nickname used by his family. There is no period evidence for this nickname aside for some references in newspaper accounts, which are frequently incorrect; so it is not certain that he was ever actually called this.

12. Birth certificate of Maud Lilian Wheeler.

13. 1901 and 1911 UK censuses. Marriage certificate for Maud Lilian Wheeler.

14. Birth certificate of Elsie Wheeler.

15. There is speculation that Emma Wheeler died shortly after childbirth of an unknown cause. Because no record of her death can be found, it may be that, when her death was registered, it was done under a misspelled name or perhaps the transcription of the record is wrong. There is also a chance that she abandoned the family and simply disappeared. Research is ongoing.

16. It seems likely that Emma Wheeler had passed away by the time of Elsie’s death in 1895 because the informant on Elsie’s death certificate was not her mother, but a Mr. Eddolls, the master of the workhouse where Elsie was living at the time.

17. Death Certificate of Frederick Wheeler.

18. Death Certificate of Frederick Wheeler.

19. Death Certificate of Elsie Wheeler.

20. Death Certificate of Elsie Wheeler.

21. Death Certificate of Elsie Wheeler.

22. 1901 UK Census. Wheeler is listed as a “boarder” at Highbury House along with 9 other boys ranging in age from 14 to 16 years as well as one 30 year old. Wheeler’s occupation is listed as “errand boy” as are most of the others with whom he was living. Among the others in the household were Edward and Sarah Powley and their son Stanley.

23. 1901 UK Census

24. Death certificate for Maud Lilian Wheeler.

25. If Wheeler had remained in the UK for another few weeks, he would have taken part in the 1911 UK Census.

26. Passenger manifest for RMS Majestic, Southampton to New York, March 29, 1911.

27. Passenger manifest for RMS Majestic, Southampton to New York, March 29, 1911.

28. “Jennie” may refer to Virginia Purdy Bacon, George Vanderbilt’s cousin.

29. The coal strike eventually ended on April 6, three days after Olympic sailed with the Vanderbilts on board, but there was not enough time for newly mined coal to be shipped to Southampton and loaded on Titanic. Coal from five International Merchant Marine ships still at Southampton and leftover coal from her sister ship Olympic had rumbled down into Titanic‘s spacious coal bunkers. She had arrived from Belfast with 1,880 tons of coal, and to this was added 4,427 tons while in Southampton.